Some Thoughts About Stalkerware and Technology in Intimate Partner Violence

A few years ago, I wrote about Flexispy after the company got hacked and some data was released. It was the first time I encountered stalkerware in my work. Since then, I have had many discussions about this creepy market and more generally technology used in intimate partner violence (IPV) with researchers and activists. I think it is the right time to reflect on what we know about stalkerware and what needs to be done on this topic.

Trigger Warning: this blog post talks about violence against women and intimate partner violence.

What is stalkerware?#

We call stalkerware (sometimes also spouseware or creepware) a malware that is used in intimate partner violence. There is a market of products available for that purpose (I have identified around 50 companies but there are likely many more), often presented as tools to monitor kid’s devices but clearly targeting intimate partner spying.

Since 2017, some interesting research has been published and several organizations have been working on this topic. Here are the ones I know and found interesting:

- the Citizen Lab has published a multi-disciplinary assessment in June 2019, called The Predator in Your Pocket which includes technical, policy and legal assessments

- Eva Galperin from EFF has done several talks about Stalkerware, including one at Enigma and a TED Talk

- The Cornell university has a research group supporting victims with technology in an organization called Clinic to End Tech Abuse (previously IPVTechResearch). They have created a clinic service for organizations working with victims and a methodology to support them. They published openly the tools and methodology they use and have published their results at several conferences. To me, it is one of the most interesting research projects today on this topic.

- A Coalition against stalkerware has been created, it includes non-profit organizations and antivirus companies.

- Several people have published interesting technical analysis such as nscrutables stalkerware analysis or ch33r10 stalkerware indicators (I have also published some indicators)

Is Stalkerware Common?#

It is quite hard to answer this question, first because we do not have a lot of data on this issue today, but also because the answer will likely be different depending on the context (country, language, social class, etc.).

On one side yes, stalkerware are giving abusers a very powerful tool to spy on their partner, but at the same time, it has a cost. A monthly cost first as they have to pay for the service, but also a cost to know how to use it, learn how to install it, etc. And today, there are so many ways to use legitimate apps already installed on phones to have access to some data for less effort (like sharing geolocation with Google Maps).

A few studies are bringing some interesting data to answer this question.

In 2014, NPR surveyed 72 domestic shelters in the US and 75% of them said they were working with victims whose abusers eavesdropped on their conversation remotely — using hidden mobile apps. In France, the Centre Hubertine Auclert has done a study in 2018 on Cyber-Violence. Based on answers from 212 victims, 29% of them said that they feel their movements are surveilled by their ex-partner using either a GPS tracker or spyware.

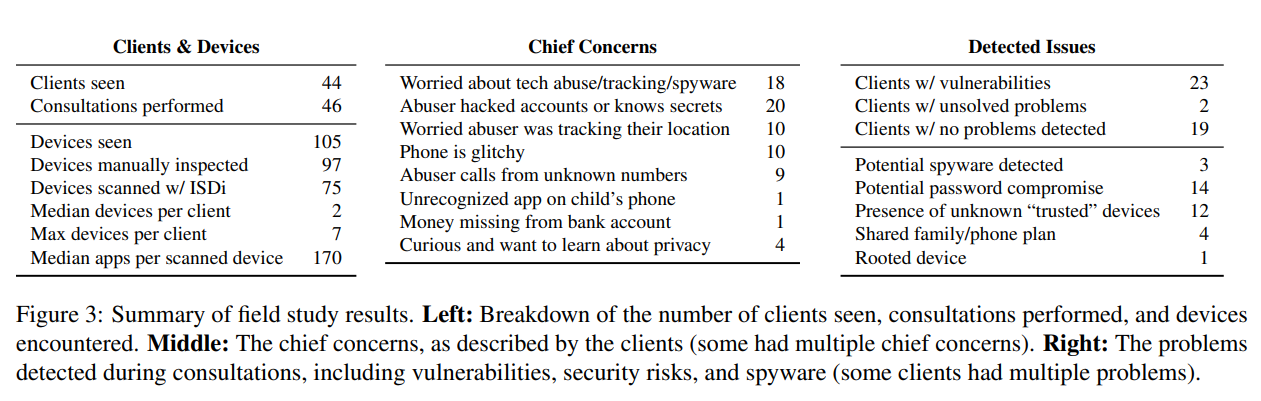

The research done by the Clinic to End Tech Abuse brings the most interesting data to me. They have supported victims in New York on technology using both interviews and technical analysis of devices looking for stalkerware. Their 2019 Usenix research paper shows the result of their support done to 46 victims:

We see here that only three of the victims had a potential spyware installed, while most of them had issues with access to their online accounts either through password compromise or connected devices. Several of them also had issues with data available through their shared phone plans.

So it seems that stalkerware is only one minor issue in the middle of so many other technology abuses in this context. In that case, why do we draw a line on stalkerware and exclude other forms of technology abuse?

The problem is violence against women#

The first time I had a discussion with a women shelter in France, I was shocked by the gap I found between the research I was reading on stalkerware and the problems this shelter was facing. They were (and still are) massively underfunded, receiving victims in very hard situations without enough people and funds to be able to help everyone as they would like to. Even worse, the Grenelles des violences conjugales (a national conference on domestic violence) organized by the French government in November 2019 raised awareness on this issue, so shelters saw an increase in victims coming to them to seek help. This was not followed by an increase in funding for organizations working with victims, often making their situation even harder.

So we should keep that in mind: the ultimate goal is to get rid of domestic violence and violence against women. All the work we can do on stalkerware and on technology in this context makes no sense if it is not aimed at doing that.

But there is a clear gap there: we as technologists, developers or hackers, do not clearly understand the entirety of the issues concerning domestic violence and how to create change on this topic. The solutions we often bring to problems (research or technical solutions) do not work here. And we often tend to fall in techno-solutionism and develop apps to solve all the issues we find (trust me, I’ve tried it). None of this will work here, it is a massive social issue that has deep roots in centuries of patriarchy, in which technology has a minor role that we do not even fully understand.

So we have to make sure that we are putting our skills and energy to support people who have experience with this issue, make sure that organizations working with victims of intimate partner violence are funded enough to do their work, and to have time to work on the technology aspect of it.

The problem of what is interesting versus what is needed#

I think another parameter that plays in that decision is the gap there is here between what is interesting and cool and what is needed. In computer research / tech, we want to analyze the interesting new threats, reverse the most recent malware or publish about the last attack scenario. First, because it is interesting and fun, there is a thrill in finding the newest cool hack that no one has ever analyzed. But also, let’s face it, because it is cool. Once you have done that work, you can present this work to different conferences and receive the peer-validation we are pretty much all looking for in some forms. This aspect not only plays a role in individual decisions but even more in company decisions to invest time and money on a topic (which I think partially explains the recent focus of the antivirus industry on stalkerware).

But the truth is that helping women to update their passwords, writing guides in simple languages, knowing the details of how to keep access to Gmail or Facebook and keep track of their so frequent changes in the interface is likely going to help way more than reversing stalkerware here.

It is not a unique issue, it also partially explains why so few people work on targeted attacks against civil society (as explained by nex in his 2016 CCC talk) or why there is such a strong focus on offensive security versus defensive security in the information security industry. It is here once again, let’s acknowledge it and make the question of what needs to be done central in our discussions on technology in intimate partner violence.

So what should we do?#

Don’t get me wrong, I am not saying we should stop research on stalkerware or stop actions to stop this creepy economy. But I think we have to be mindful of not creating technical communities disconnected from organizations working on violence against women and domestic violence.

I see three important directions to do that:

- We should focus our work on making sure that technology in general is not used in abusive relationships. This includes fighting against stalkerware, but I see little reason to focus only on stalkerware.

- The work we do should be connected as much as possible with organizations working on violence against women and domestic violence to make sure that the solutions we bring are relevant to them. They know what is happening, they work with victims, they are the experts here and we are only helping on a small subset of their issues.

- When possible, let’s help these organizations beyond these questions: we have money in tech, let’s support them financially, let’s help them have decent computers, help them spend less time on things we know (websites, emails etc.) so that they can spend more time supporting victims. There is no legitimate reason why tech people get so much money for their work while social workers often get minimum wage, let’s reroute part of that money to these organizations and people who often put their whole energy in their work.

Over the past weeks, I have read many research papers studying how technology is used in domestic violence and I have started an online collaborative bibliography on this topic called IPVTechBib. I hope it will facilitate further research for others to work on this topic more easily. Contact me or open an issue if you see a paper or article missing.

Let’s get to work.